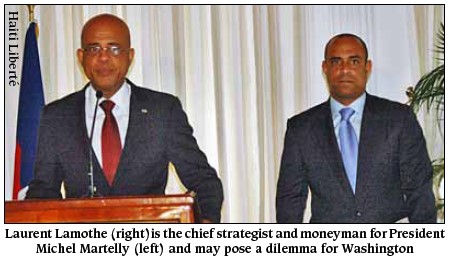

Laurent

Lamothe is Haitian President Michel Martelly’s brain, just as

political strategist Karl Rove was to former U.S. President

George W. Bush. Laurent

Lamothe is Haitian President Michel Martelly’s brain, just as

political strategist Karl Rove was to former U.S. President

George W. Bush.

Lamothe was the guy who figured

out how to finance Martelly’s presidential campaign, and who

brought in the professional Spanish public relations firm Ostos

& Sola to run it. Now he is President Martelly’s nominee to be

Haiti’s next prime minister.

“The man is a financial

genius,” exclaimed musician Richard Morse, who manages

Haiti’s famed Oloffson Hotel and is Martelly’s cousin and part

of the president’s inner circle. “He knows how to take a

little from over here, a little from over there, put it together

with this over here, and make it all work out.”

Lamothe’s prowess for financial

wheeling and dealing stands out when one reviews his business

history with Martelly over the past decade.

Lamothe, 39, has been close to

Martelly since 2002 when he recruited the former lewd konpa

singer known as “Sweet Micky” to be a partner and the

advertising front-man for NoPin Long Distance, a calling-card

alternative service which became wildly popular in Haiti and

spawned several imitators. In fact, according to Florida State

corporate records, the original name of One World Telecom, Inc.,

the parent company of NoPin, was “Sweet Micky Long Distance

Services, Inc.”

Lamothe, along with fellow

NoPin founders Patrice Baker and Gilbert Pasquet, were all

directors with Martelly in another Florida corporation, Coco

Grove Holdings, Inc., of which Martelly was made president in

2008. Coco Grove Holdings, in turn, was owned by a British

Virgin Islands shell corporation, Lightfoot Ventures Limited,

again directed solely by Lamothe and Martelly.

Lamothe learned his financial

skills studying business management at Miami’s Barry University

and later earning a Masters in the field at another Miami

Catholic school, St. Thomas University. In Haiti, he went to

high school at the College Bird.

Born in Port-au-Prince on Aug.

12, 1972, he, like his older brother Ruben, became a Davis Cup

tennis player in 1994 and 1995, representing Haiti. But, while

his brother stayed in the sport, the lure of business drew

Laurent away.

In the late 1990s, he tried to

start up a business importing wood to Haiti from Suriname’s

Amazon forest, but that never took off.

So in 2000, Lamothe launched

Global Voice Telecom, Inc. with tennis buddy Patrice Baker.

While his business in Haiti thrived, he also made inroads into

Latin America and Africa, being fluent in both French and

Spanish. He built Global Voice into a major telecommunications

player, especially in the Third World, and became very wealthy,

keeping pricey homes in Cape Town, South Africa, and Miami,

Florida.

But he began making enemies as

well. The France-based website Le Griot.info published a

Nov. 11, 2010 article charging that Senegal’s president

Abdoulaye Wade had been “manipulated by Laurent Lamothe... to

be able to establish Global Voice in Senegal.” Lamothe “corrupted

the authorities with sums of money and voyages to South Africa

arranged by him, to have passed the project of the presidency,”

the journalist Steven Addamah asserted. “Several people

including a minister, an advisor of the president, a woman

senator, and a Director General should make $29 million on the

backs of the Senegalese taxpayers and Sonatel (the national

telephone company) after signing the contract.”

In July 2011, another

Senegal-based website, Dakaractu.com, reported similar charges

of Global Voice corruption, in countries across Africa,

including the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Guinea, and the

Central African Republic. “In Gambia, where there reigns a

despot as absolute as he is predatory, [Lamothe] managed to get

the telecom market through a deal ensuring that Yaya Jammeh, the

strongman of the country, gets millions of dollars into his

personal account and that the telephone communications of

Gambians is monitored by his listening devices,” journalist

Cheikh Yérim Seck wrote.

Global Voice formally denied

the second article, which was reprinted in Haïti Liberté,

saying that the “slanderous article” was filled with “gossip

and lies” in “an attempt to destroy Laurent Lamothe’s

reputation” and “damage Global Voice Group’s image.”

Lamothe’s nomination for PM

will now go before the Haitian Parliament for ratification. His

first, and highest, hurdle will be to prove that he meets the

Haitian Constitution’s residency requirement, under which the

prime minister must have continuously lived in Haiti for the

past five years. This provision has disqualified several PM

nominees over the years, and almost sank the nomination of Garry

Conille, Martelly’s first prime minister who resigned Feb. 24

after only four months on the job (see Haïti Liberté,

Vol. 5, No. 33, 02/29/2011). (Conille only avoided the pitfall

because his overseas residency as an NGO official was equated

with being on diplomatic assignment, although it was nothing of

the sort.)

Another hurdle will be that

Lamothe has been Suriname’s Honorary Consul to Haiti in recent

years. Martelly’s first PM nominee, Daniel Rouzier, was felled

in part because he was an Honorary Consul for Jamaica in Haiti.

There are also charges that

Lamothe may hold foreign citizenship, which the Constitution

also forbids for the post. A Special Senate commission is

looking into the double-nationality charges against him,

Martelly and 37 other high government officials.

Lamothe, who acted as Haiti’s

Foreign Minister under Conille, has two young daughters by a

Colombian woman, all living in Miami, Florida, but his current

girlfriend is said to be Stéphanie Balmir Villedrouin, the

current Tourism Minister.

Lamothe’s father, Louis, was

the founder of the Lope de Vega Institute, a school in

Port-au-Prince which teaches Spanish and promotes links to the

Spanish-speaking world. During the Duvalier and post-Duvalier

dictatorships, the senior Lamothe often sponsored scholarships

for Haitian soldiers to be trained in Latin American countries,

for example on Ecuador’s Manta Air Base where the U.S. military

was also based. (In 2009, Ecuadorian President Correa closed the

U.S. base there.) 2004 coup leader Guy Philippe and several

other Haitian soldiers were trained in Ecuador during the

1991-1994 coup.

What is Washington’s reaction

to Lamothe’s nomination? So far it is muted, which suggests that

the reaction is mixed. On the one hand, Lamothe is

pro-capitalist and an architect of the Martelly government’s

“Haiti is open for business” campaign to attract foreign

investment. That he went to school in the U.S. and operated

businesses there will also work in his favor.

However, Lamothe is not

Washington’s man, as Conille was. He belongs to Martelly. He and

the president are, as Haitians say, kokott ak figaro, two

peas in a pod. This troubles Washington, since Martelly and his

clique have displayed neo-Duvalierist tendencies, being

unpredictable and uncontrollable in making their own policies,

for instance, their initiative to reestablish the Haitian Army,

demobilized by former President Jean-Bertrand Aristide in 1995.

This is seen as a challenge to the U.S., which controls,

ultimately, the UN force known as MINUSTAH which has militarily

occupied Haiti since the 2004 coup against Aristide.

Most alarming for Washington,

though, is that Lamothe and Martelly have shown a troubling

tendency, as their predecessors did, of dealing closely and

warmly with Cuba and, particularly, Venezuela. They have

reinforced Haiti’s participation in ALBA, the anti-imperialist

trade front led by Venezuela and Cuba. In fact, ALBA was to meet

for the first time in Haiti, in the southeastern town of Jacmel

on Mar. 2-3; it was to be a conclave of ALBA foreign ministers.

But at the last minute, the

meeting was postponed without explanation until April, and moved

tentatively to Port-au-Prince. Nonetheless, on those dates,

Lamothe hosted Venezuela’s Vice Minister of Foreign Affairs and

Curacao’s Prime Minister for a Summit of Haiti-Venezuela

Solidarity, which he called a “testimony to the

indestructible and immovable friendship between the peoples of

Haiti and Venezuela.” Saying that Venezuela remembers the

contributions Haiti made to the anti-colonial revolutions on the

continent, Lamothe announced that Venezuela “intends to

further strengthen its ties with Haiti by multiple bilateral

cooperation covering all areas, both economic, social, cultural,

agro industrial, commercial, educational, humanitarian and

other,” and that “South-South cooperation is crucial for

the development of Haiti.” That’s an awful lot of red flags.

Lamothe tried to reassure

Washington this week, telling the Haiti Press Network that “Haiti

is not in a position to make a political about-face, we are

simply need to provide assistance to a population that has been

neglected for 208 years.”

To drive the point home, he

assured that “the United States is and remains Haiti’s

greatest partner; we are working on several projects. We have

tremendous respect for what the U.S. does in Haiti. There is no

estrangement, but we inherited a series of relationships which

we have revitalized.”

Conille had asked Martelly to

publish Haiti’s amended constitution, which allows the Prime

Minister to replace the President if he has to step down.

Martelly knew the game that Conille and Washington were up to

and refused to set the stage for Conille to replace him.

However, last week, Bill and Hillary Clinton’s long-time agent,

Cheryl Mills (presently Hillary’s chief of staff), flew to

Port-au-Prince to put pressure. Martelly agreed to publish the

amendments... as soon as the prime minister, his prime

minister, is ratified.

Meanwhile, Haitian

parliamentarians have said that they will not ratify any nominee

until Martelly cooperates with their double-nationality

investigation, at which he has been thumbing his nose.

Will the U.S. hold out to see

their own candidate, a technocrat like Conille, become the PM

nominee, or will they take a chance with Lamothe?

Will Parliamentarians stand

firm on their promise to not budge until Martelly bows, or will

they succomb to Martelly’s bribes and bluster?

Stay tuned during the next few weeks for the answer. |

No comments:

Post a Comment